CSCAA Newsletter // November 2019

CSCAA Newsletter // November 2019

Coaches, it’s great to be back for part three of this series on mental health – a subject that impacts all of us both professionally and personally. For every five coaches standing alongside us on the pool deck or sitting across from us in a faculty meeting, there’s one (or more) who’s navigating mental illness; this isn’t just an athlete thing – it’s a human thing. The skills and supports shared in this series can help all of us grow our awareness, release the grip of stigma, strengthen our emotional agility and get the help we need so we can thrive in all areas of our lives. If we want to help our athletes elevate their mental health and improve their performance, it starts with us.

With the recent launching of the #lookafteryourcoach initiative aimed at the mental well-being of coaches across all sports, I thought it appropriate to turn our focus to an area that typically generates rich dialogue and is connected to mental health problems on both sides: coach + athlete.

This month we’re focusing on navigating feedback. I’m going to share ground rules that can help us move to the space where empathy, high expectations and accountability can coexist. As you know, coaching is an art – likewise, so is the giving and receiving of feedback. With time, practice and the willingness to do hard things, we can grow this skill set and help our athletes do the same.

Have you ever found yourself in a situation where what you said and what was heard were not one in the same?

Given that feedback is fundamental to coaching, I’m guessing the chances are pretty high. While there’s no singular answer to why messages are missed, my goal in this pieces is to share a few things that can help improve communication, alleviate stress, drive connection, elevate mental well-being and enhance performance.

To be clear, our work as coaches isn’t in refining our communication skills to the point of perfection. We’re going to miss the mark at times because, we’re human. Our words aren’t always going to land the way we want them to. We are going to mess up - and say the ‘wrong’ things at times. And. That’s not a free pass to sling shame. As coaches, our words and actions hold power and impact our athletes. Our goal then is to control what we can, and create a culture where coaches and athletes turn toward hard conversations in a way that’s aligned with the values of the team.

So, let’s start there.

What are the values of your team?

Brené Brown, a research professor at the University of Houston and New York Times bestselling author, has spent the past two decades studying courage, vulnerability, shame, and empathy. Her work has had a profound impact on my life – and given me the tools and language to sift through feedback, without shutting down or moving into judgement, shame and blame. Big work for a recovering perfectionist.

In her latest book, Dare to Lead, she defines a value “as a way of being or believing that we hold most important. Living into our values means that we do more than profess our values, we practice them. We walk our talk – we are clear about what we believe and hold important, and we take care that our intentions, words, thoughts, and behaviors align with those beliefs.”

I grew up believing that to be loved, I had to be perfect. As a child of the self-esteem movement, the thought of being average was an insult. Like so many who grew up impacted by this nation-wide push to make our kids feel special, my accomplishments were tied to my self-worth, driving a need to feel ‘better than’ and contorting messages so that what I heard and what was said weren’t always the same.

When I was ahead and achieving, and the feedback was positive, I felt great. When the feedback was constructive or critical, I shrank.

When our identity becomes intertwined with our accomplishments, our sense of self stays in constant flux causing us to live in fear of other people’s opinions.

We become dependent on feedback as a means of measuring our worth.

Failures become more than opportunities and moments of falling short — they become evidence that we are not enough.

Which is exactly what I heard when I went out to Colorado Springs a year before the 2000 Olympic Trials. While there, they did all sorts of testing – capturing and quantifying data, filming and psychological assessments. After the filming session, I was told that my freestyle was > 99% efficient and so, to get faster (and give myself a shot at making the Olympic Team), I had to lose weight and maintain my strength or gain strength and maintain my weight.

Any guesses what my 17 year-old-self heard?

You’re fat. You need to lose weight.

What my coach heard:

She’s got this. If you want to help her go faster, here’s one way: increase her strength-to-body weight ratio.

Except, we never talked about it.

Not a single word.

The silence created room for meaning-making not based in reality, and shame crept in. We went back to work. Head down. Plowing through. Fighting for the same goal.

My logbooks transitioned from capturing workouts, tempos, pacing and reflections to capturing my obsession with food – which eventually led to an eating disorder that could have killed me. Eating disorders are not just about food, weight, appearance or willpower; they are serious and potentially life-threatening illnesses. Eating disorders have the highest death rate of all mental illness.

An important note about eating disorders: Though most athletes with eating disorders are female, male athletes are also at risk—especially those competing in sports that tend to emphasize diet, appearance, size and weight. In weight-class sports (wrestling, rowing, horseracing) and aesthetic sports (bodybuilding, gymnastics, swimming, diving) about 33% of male athletes are affected. In female athletes in weight class and aesthetic sports, disordered eating occurs at estimates of up to 62%.

I don’t write to place blame. I write to pay forward what I know now – and what I wish I knew back then, in hopes it can make an impact.

The World Health Organization defines mental health as a "state of well-being in which the individual realizes their own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to their community.”

Mathematically, it’s not possible for all of our athletes to be above average in all the things, and yet – for various reason (snowplow parenting, inflated grades + GPAs, participation trophies, banning of red pens and ranking, self-protection, etc.), many have never learned how to positively cope with emotional pain, which severely limits their ability to give and receive feedback. Not to mention, the ‘normal’ stresses of life today are different than they were even just a decade ago.

In the athletic arena, give us all the physical pain – we can do that – but the minute we feel uncomfortable emotions, we want out. (I know I’m overgeneralizing here.) Growing our awareness of our internal world - our thoughts, emotions and behaviors - allows for greater self-regulation which elevates mental health and improves performance.

Work that needs to happen on both sides: coach + athlete.

How does that relate to feedback? The simplest answer:

If you’re giving me feedback that elicits any kind of uncomfortable emotion – especially if my self-worth is tied to achievement (or perfection), I am ill equipped to handle it; I cannot hear you.

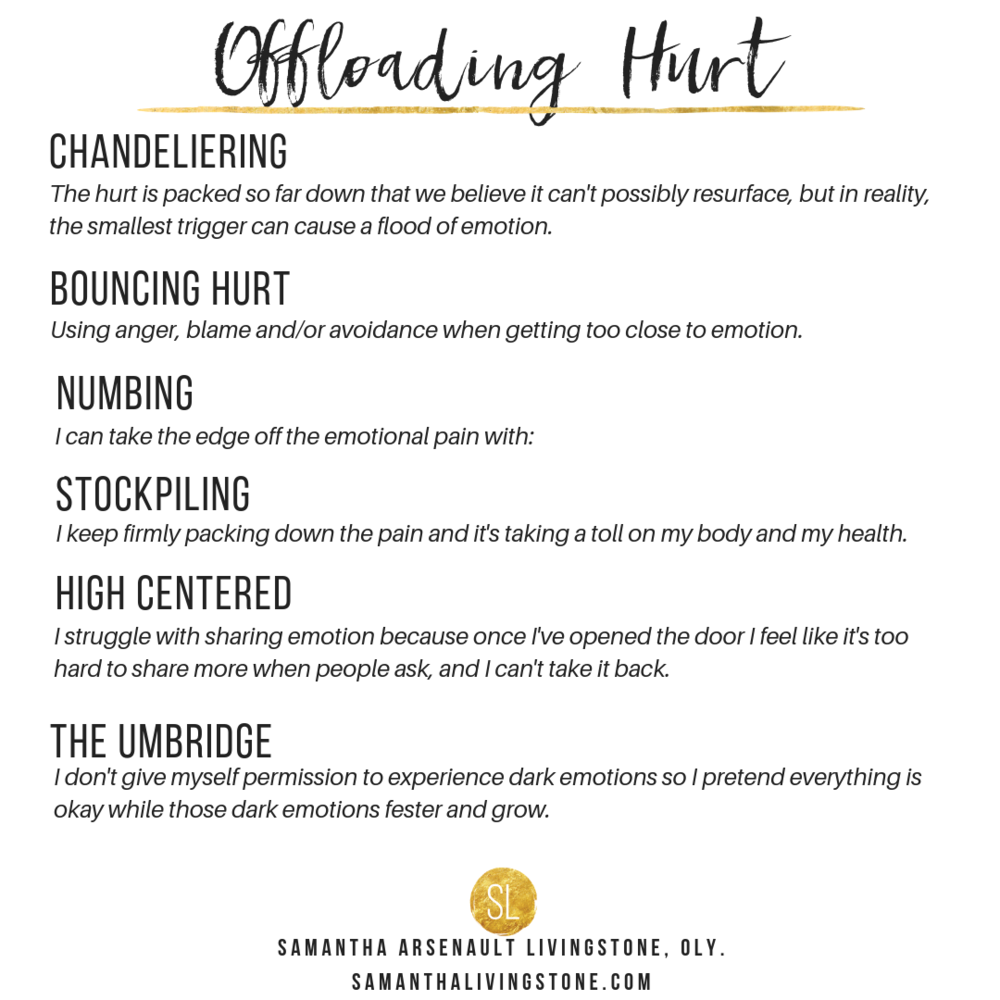

Cue judgement, blame, shame and all the offloading strategies.

We’re facing unprecedented levels of mental illness; levels that continue to rise, according to the latest report from the CDC released last month. And then there are the unintended consequences of the self-esteem movement seen in the rising levels of narcissism and waning of empathy — driving isolation, separation and self-enhancement bias (puffing ourselves up and putting others down so we can feel superior). All of it is impacting your team in some capacity.

And what I keep hearing is that when it comes to providing feedback, you’re stressed + stuck.

Because, you don’t know how to say it without offending someone.Because, you fear you might make it worse. Because, you’re afraid of being misunderstood by both athletes and administration.Because, you’re tired of dealing with parents and putting out fires. (And thought that would’ve been over by now.)

And, you still show up every day. Ready to help your athletes achieve their goals, in and out of the pool. Ready to help them as humans, first, and then as students and athletes.

Sometimes at the cost of your own mental health. My intention in sharing the following ground rules is to help lift a bit of that burden. In order to turn toward hard conversations, we’re going to have to build those courage muscles – and do hard things. As coaches, this begins by acknowledging the power of our words. We must walk-the-walk WITH our athletes to become courageous, mindful, resilient leaders.

HERE ARE GROUND RULES FOR NAVIGATING FEEDBACK:

Ground Rule: Unhook yourself first.

Before we move into a conversation, it’s helpful to check-in with ourselves to see if there’s anything we need to do to show up fully. How are we coping with our own thoughts and emotions? What helps us when we’re feeling upset? HALT is a great acronym to remember and pass on — hungry? angry? lonely? tired? If so, tend to those needs first before moving to the conversation, which leads us back to the #lookafteryourcoach initiative. What are you doing to take care of yourself? How are you elevating your own mental health? We cannot pour from an empty cup. We can try, but something will suffer. Honoring your health isn’t selfish, it’s necessary.

Ground Rule: Feedback is an opportunity for growth, not a comment on your self-worth.

Communicate this message early and often. Let your athletes know that it’s OK to feel. And. Be explicit about drawing boundaries around behavior — what’s OK and what’s not. We can listen with empathy - honor what our athletes are feeling AND still hold high expectations for their behavior. It’s OK to feel frustrated and angry; it’s not OK to throw your emotions onto others. It’s OK to feel disappointed; it’s not OK to skip practice. It’s OK to feel jealous; it’s not OK to cut up teammates. It’s important to acknowledge what they’re feeling - even if you don’t understand why. We can’t always control what emotions we get hit with, we can control how we respond. We are responsible for our behavior even if/when their are contributing factors underneath the surface beyond our control. If their behavior isn’t in alignment with team values, have a discussion about what supports they may need to show up in alignment. They may need new skills. If they are having trouble coping with the pressure or emotions that surface, that’s a sign that they may need the supports of mental health professionals. Remember, early intervention is a high predictor of wellness and recovery.

Ground Rule: Shift Away From Shame

As coaches, we hold a powerful position. We have direct access to our athlete's inner circle of feedback - especially about their physical bodies.

One of the most critical pieces in all of this is making sure our kids KNOW that they are loved, exactly as they are. And for some of us, that may mean shifting how we show up. Let me be clear: This isn’t about going easy on our kids - or trying to show up in a way that protects them from pain - or remove all accountability; it’s just the opposite.

When we use shame as a mechanism to deliver feedback, we miss in big ways.

They can’t hear us. And it corrodes their mental health.

In a recent workshop I facilitated, a group of coaches were talking about ways to really know what their athletes were hearing. One coach in particular started squirming into a bit of a shame spiral for the way he’s been showing up on deck. He recognized that he was great at giving feedback, but had no idea how it was landing. He also recognized that he was giving feedback without a clear separation of human + behavior - which can be harmful.

His courage in sharing inspired all of us, truthfully. Because we have all showed up in ways we wish we hadn’t.

That doesn’t mean he’s a bad coach or bad human.

In fact, in that moment we all saw how much he cared.

For most of us out there doing the best we can with the tools we have, the slide from guilt to shame is instantaneous, especially when we don’t know the difference.

The former is behavior-focused and it’s a heavy and hard feeling to navigate because we can’t go back and undo what we did. It’s also a motivator for change — we can’t go back and change how we showed up, but we can learn from it. The latter shuts us down. Shame is a powerful, master emotion that silences and isolates.Guilt says, I made a bad choice. Shame says, I am bad.Guilt asks us to change our behavior. Shame tells us we’re not enough.

Just as this recognition of separation of behavior + self is critical for our kids, it’s also critical for us too.

Because research tells us that shame is connected to and a driver of mental illness and suicide.The coach recognized that his behavior - the cutting up + leaning into an athlete - was / is damaging. We talked about a different way to show up + how to respond differently if (not when) we step outside of alignment again.Because, we all do.

Ground Rule: Create Space for Story-Busting

Our brains seek order and pattern and complete stories — so where there are gaps in information, there are assumptions. The thing with mental illness is that it can sometimes stop us from asking for what we need. One of my favorite lines, adopted from Brené, is ‘The story I’m telling myself….” Ask your athletes to reflect back to you what they heard. If you feel like you missed, say something. I’m not sure if I articulated that well, can you tell me what you heard? Sticking to first person helps. When we lead with YOU, people tend to get defensive and shut down.

Ground Rule: “Nobody cares how much you know, until they know how much you care.” -Theodore Roosevelt

Until next time! Here’s a challenge for you: In your next staff meeting, check in with each other to see how things are going on the self-care front and then share ways you unhook from big emotion — ways that soothe AND serve.

Need help unhooking? Fill out the form below and I’ll send you a printable version of my newest mini deep dive, Riding the Wave, for you + your team — as always, I love hearing from you: samantha@samanthalivingstone.com

//

Samantha Arsenault Livingstone is an Olympic Gold Medalist, high-performance consultant, mental performance coach, speaker, educator and entrepreneur. She is the founder of Livingstone High Performance, LLC., the two, multi-module online courses — inspiring, empowering and equipping athletes, coaches and female leaders with the skills they need to become more mindful, courageous, resilient leaders. In addition to private and group coaching, Samantha consults with teams and organizations on athlete wellness, Mindful Sport Performance Enhancement (MSPE), leadership, strategic planning, rising skills and developing high-performance cultures.

Join Samantha in the I AM CHALLENGE private community space to link arms, connect + participate in her free challenges.

A mama of heart warrior and mama of twins, Samantha and her husband, Rob, live in the Berkshires with their four girls. To learn more about her offerings, go over to www.samanthalivingstone.com or email her at samantha@samanthalivingstone.com.